Unofficial - F5 Certification Exam Prep Material > F5 101 - App Delivery Fundamentals Exam Study Guide - Created 03/06/20 Source | Edit on

Section 1 - Configuration¶

The setup and configuration of an F5 device requires a solid understanding of network infrastructure and how networks are designed and built. It doesn’t matter if you are deploying an F5 appliance in a private data center, an F5 Viprion chassis in a private cloud or an F5 virtual edition in the public cloud, you need to have a mastery of networking. Even in today’s agile IT landscape where infrastructure is code and the ability to deploy F5 infrastructure on bare metal using F5 Declarative Onboarding (DO) or other tools like Hashicorp’s Terraform is common place, you can’t write the code to automate the build on the network if you don’t understand how networks work.

Objective - 1.01 Explain, compare, and contrast the OSI layers¶

1.01 – Given a set of requirements, configure VLANs

https://clouddocs.f5.com/cli/tmsh-reference/v13/modules/net/net-vlan.html

Configuring VLANs in BIG-IP

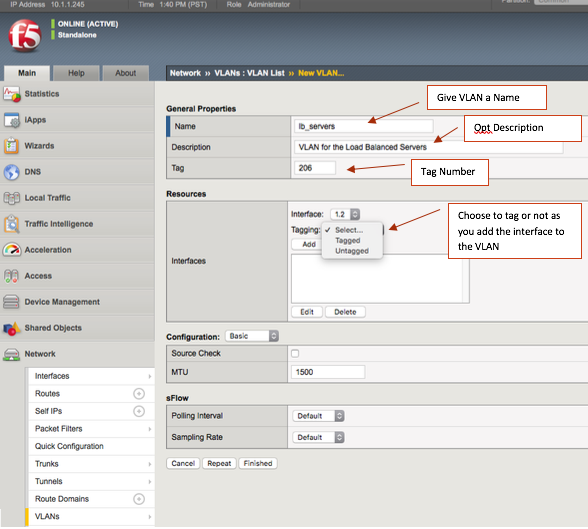

There are many different deployment scenarios that will each demand their own unique configuration and this content in the TMOS Implementations link will go over a few of them. This exam will possibly provide a deployment scenario and ask how to create or modify a VLAN to meet the scenario requirements. An exam candidate should understand that if the setup wizard is used in the BIG-IP GUI it is going to create two VLANs named External and Internal. This two VLAN configuration is a simple type of deployment that can be used in labs and is a great way to depiction the network flow in a full proxy architecture operating system like BIG-IP TMOS, but it is not always what is needed in the real world. An exam candidate should be aware of how to create VLANs in the GUI without using the wizard and also using TMSH Command Line. There are examples in the F5 Clouddocs link and more on the F5 Support website. For me, VLANs should be created on the BIG-IP with a descriptive name and tag numbers that match the descriptive name and tag number in the connected Layer-2 switch. VLAN Tagging will not necessarily be enabled but the tag number will be configured in the switch and can also be configured in the BIG-IP even with tagging disabled.

1.01 – Assign a numeric tag to the VLAN if required

Assigning a tag number to the vlan

About tagged interfaces

You can create a VLAN and assign interfaces to the VLAN as single- or double-tagged interfaces. When you assign interfaces as tagged interfaces, you can associate multiple VLANs with those interfaces.

A VLAN tag is a unique ID number that you assign to a VLAN, to identify the VLAN to which each packet belongs. If you do not explicitly assign a tag to a VLAN, the BIG-IP system assigns a tag automatically. The value of a VLAN tag can be between 1 and 4094. Once you or the BIG-IP system assigns a tag to a VLAN, any message sent from a host in that VLAN includes this VLAN tag as a header in the message.

Important: If a device connected to a BIG-IP system interface is another switch, the VLAN tag that you assign to the VLAN on the BIG-IP system interface must match the VLAN tag assigned to the VLAN on the interface of the other switch.

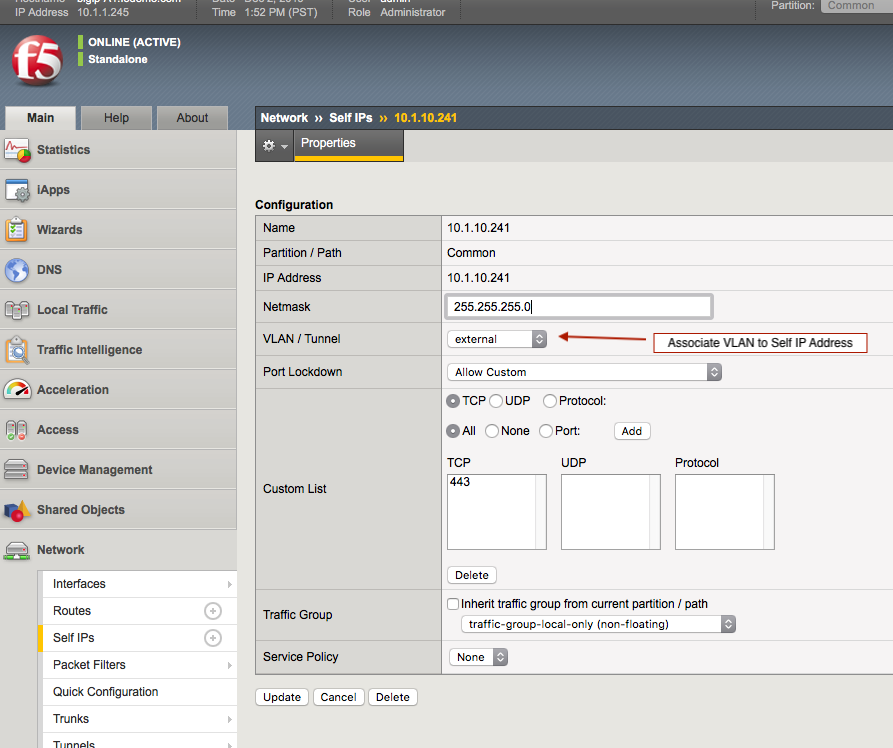

1.01 - Determine appropriate layer 3 addressing for VLAN

Layer 3 addressing for VLAN

Normally in the OSI model, the term VLAN is a Layer 2 configuration object and IP Addressing is a Layer 3 configuration object. What is meant by this Objective Example is when a BIG-IP has a Layer 2 VLAN configured, it must also have an IP address on the Layer 3 IP subnet associated to that VLAN to participate in the network communications. If there are two BIG-IP units in an HA pair each using must have a unique IP in the IP subnet on that VLAN as well as a shared IP that will float to the active unit in the pair.

The only time the BIG-IP would not have an IP associated to the VLAN is if the associated VLAN interface ports are to be used to bridge a Layer 2 VLAN through the F5 device. This is a rare configuration case and essentially makes the BIG-IP a simple Layer 2 switch for those ports associated to the VLAN.

VLAN association with a self IP address

Every VLAN must have a static self IP address associated with it. The self IP address of a VLAN represents an address space, that is, the range of IP addresses pertaining to the hosts in that VLAN. When you ran the Setup utility earlier, you assigned one static self IP address to the VLAN external, and one static self IP address to the VLAN internal. When sending a request to a destination server, the BIG-IP system can use these self IP addresses to determine the specific VLAN that contains the destination server.

The self IP address with which you associate a VLAN should represent an address space that includes the IP addresses of the hosts that the VLAN contains. For example, if the address of one host is 11.0.0.1 and the address of the other host is 11.0.0.2, you could associate the VLAN with a self IP address of 11.0.0.100, with a netmask of 255.255.255.0.

1.01 - Specify if VLAN is tagged or untagged

Setting VLANs as Tagged or Untagged

There can be confusion on this topic, especially if you have a Cisco background. What F5 calls “VLAN tagging”, Cisco calls “Trunking”. The difference in configuration naming standards is not what causes the confusion because regardless of the descriptive name they both mean the same thing. The system is following the 802.1q standard and adding a 4-byte VLAN tag value to the Ethernet frame that will allow the upstream switch as well as the BIG-IP to determine the correct VLAN to place an incoming frame onto when received, thus providing the capability to pass more than one VLAN’s traffic on the interface. The confusion comes in when we start to discuss Link Aggregation. Cisco calls link aggregation a “Port Channel” and F5 calls it “Trunking”.

About untagged interfaces

You can create a VLAN and assign interfaces to the VLAN as untagged interfaces. When you assign interfaces as untagged interfaces, you cannot associate other VLANs with those interfaces. This limits the interface to accepting traffic only from that VLAN, instead of from multiple VLANs. If you want to give an interface the ability to accept and receive traffic for multiple VLANs, you add the same interface to each VLAN as a tagged interface.

About tagged interfaces

You can create a VLAN and assign interfaces to the VLAN as single- or double-tagged interfaces. When you assign interfaces as tagged interfaces, you can associate multiple VLANs with those interfaces.

A VLAN tag is a unique ID number that you assign to a VLAN, to identify the VLAN to which each packet belongs. If you do not explicitly assign a tag to a VLAN, the BIG-IP system assigns a tag automatically. The value of a VLAN tag can be between 1 and 4094. Once you or the BIG-IP system assigns a tag to a VLAN, any message sent from a host in that VLAN includes this VLAN tag as a header in the message.

Important: If a device connected to a BIG-IP system interface is another switch, the VLAN tag that you assign to the VLAN on the BIG-IP system interface must match the VLAN tag assigned to the VLAN on the interface of the other switch.

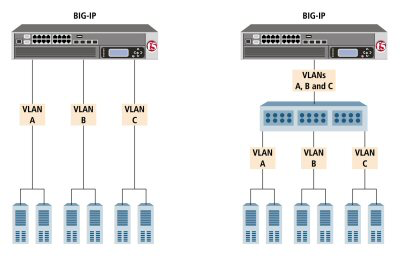

About single tagging

This figure shows the difference between using three untagged interfaces (where each interface must belong to a separate VLAN) versus one single-tagged interface (which belongs to multiple VLANs).

Solutions using untagged (left) and single-tagged interfaces (right)

The configuration on the left shows a BIG-IP system with three internal interfaces, each a separate, untagged interface. This is a typical solution for supporting three separate customer sites. In this scenario, each interface can accept traffic only from its own VLAN.

Conversely, the configuration on the right shows a BIG-IP system with one internal interface and an external switch. The switch places the internal interface on three separate VLANs. The interface is configured on each VLAN as a single-tagged interface. In this way, the single interface becomes a tagged member of all three VLANs, and accepts traffic from all three. The configuration on the right is the functional equivalent of the configuration of the left.

Important: If you are connecting another switch into a BIG-IP system interface, the VLAN tag that you assign to the VLAN on the BIG-IP system must match the VLAN tag on the interface of the other switch.

About double tagging (This functionality is rarely used in Enterprise architectural design)

For BIG-IP systems with ePVA hardware support, the system includes support for the IEEE 802.1QinQ standard. Known informally as Q-in-Q or double tagging, this standard provides a way for you to insert multiple VLAN tags into a single frame. This allows you to encapsulate single-tagged traffic from disparate customers with only one tag.

Double tagging expands the number of possible VLAN IDs in a network. With double tagging, the theoretical limitation in the number of VLAN IDs expands from 4096 to 4096x4096.

When you implement double tagging, you specify an inner tag that encapsulates all of the single-tagged traffic. You then designate all other tags as outer tags, or customer tags (C-tags), which serve to identify and segregate the traffic from those customers.

A common use case is one in which an internet service provider creates a single VLAN within which multiple customers can retain their own VLANs without regard for overlapping VLAN IDs. Moreover, you can use double-tagged VLANs within route domains or vCMP guests. In the latter case, vCMP host administrators can create double-tagged VLANs and assign the VLANs to guests, just as they do with single-tagged VLANs. For a vCMP guest running an older version of the BIG-IP software, double-tagged VLANs are not available for assignment to the guest.

Note: On systems that support double tagging, if you configure a Fast L4 local traffic profile, you cannot enable Packet Velocity Asic (PVA) hardware acceleration.

Objective - 1.02 Given a scenario, determine switch, router, and application connectivity requirements¶

1.02 - Explain the function and purpose of a router, of a firewall and of a switch

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Router_(computing)

Routers

A router is a networking device that forwards data packets between computer networks. Routers perform the traffic directing functions on the Internet. Data sent through the internet, such as a web page or email, is in the form of data packets. A packet is typically forwarded from one router to another router through the networks that constitute an internetwork (e.g. the Internet) until it reaches its destination node.

A router is connected to two or more data lines from different IP networks. When a data packet comes in on one of the lines, the router reads the network address information in the packet header to determine the ultimate destination. Then, using information in its routing table or routing policy, it directs the packet to the next network on its journey.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Router_(computing)

Firewalls

In computing, a firewall is a network security system that monitors and controls incoming and outgoing network traffic based on predetermined security rules. A firewall typically establishes a barrier between a trusted internal network and untrusted external network, such as the Internet.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Router_(computing)

Switches

A switch is a device in a computer network that connects other devices together. Multiple data cables are plugged into a switch to enable communication between different networked devices. Switches manage the flow of data across a network by transmitting a received network packet only to the one or more devices for which the packet is intended. Each networked device connected to a switch can be identified by its network address, allowing the switch to direct the flow of traffic maximizing the security and efficiency of the network.

A switch is more intelligent than an Ethernet hub, which simply retransmits packets out of every port of the hub except the port on which the packet was received, unable to distinguish different recipients, and achieving an overall lower network efficiency.

An Ethernet switch operates at the data link layer (layer 2) of the OSI model to create a separate collision domain for each switch port. Each device connected to a switch port can transfer data to any of the other ports at any time and the transmissions will not interfere.[a] Because broadcasts are still being forwarded to all connected devices by the switch, the newly formed network segment continues to be a broadcast domain. Switches may also operate at higher layers of the OSI model, including the network layer and above. A device that also operates at these higher layers is known as a multilayer switch.

Segmentation involves the use of a switch to split a larger collision domain into smaller ones in order to reduce collision probability, and to improve overall network throughput. In the extreme case (i.e. micro-segmentation), each device is located on a dedicated switch port. In contrast to an Ethernet hub, there is a separate collision domain on each of the switch ports. This allows computers to have dedicated bandwidth on point-to-point connections to the network and also to run in full-duplex mode. Full-duplex mode has only one transmitter and one receiver per collision domain, making collisions impossible.

The network switch plays an integral role in most modern Ethernet local area networks (LANs). Mid-to-large sized LANs contain a number of linked managed switches. Small office/home office (SOHO) applications typically use a single switch, or an all-purpose device such as a residential gateway to access small office/home broadband services such as DSL or cable Internet. In most of these cases, the end-user device contains a router and components that interface to the particular physical broadband technology. User devices may also include a telephone interface for Voice over IP (VoIP).

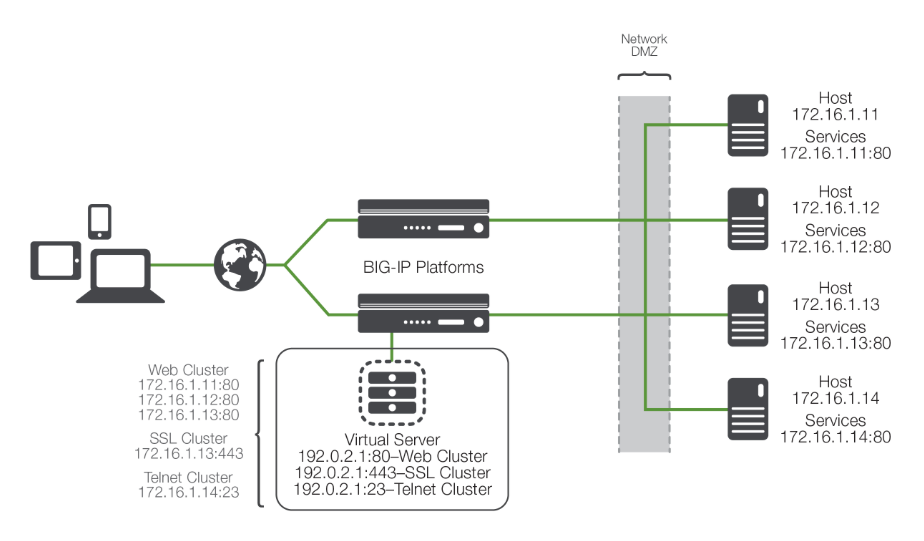

1.02 - Interpret network diagrams

Interpret network diagrams

Network diagrams visualize the components involved in a computer network and their connections, which can include a wide variety of both generic and specific symbols.

An example may look like this:

Network diagrams will be used on this exam to represent question scenarios and as basic reference information for questions. The ability of a candidate to assess the presented diagrams, comprehend the information they provide and apply the information to the questions is critical.

Objective - 1.03 Given a set of requirements, assign IP addresses¶

1.03 - Given a set of requirements, assign IP addresses

Assigning IP Addresses

There are many different deployment scenarios that will each demand their own unique configuration and this content in the Techdocs will explain the types of IP addresses needed by the BIG-IP system. This exam will possibly provide a deployment scenario and ask how to assign IP addresses to the BIG-IP system. BIG-IP systems can have multiple IP addresses because the system can and usually does have a presence on multiple networks. The out-of-band management interface requires an IP address. The BIG-IP will have an IP address on each VLAN it is configured to participate on as well as a floating IP, if it is a part of an HA pair. This was discussed in section 1.01 of this document. A functional IP address may have to be determined from a diagram that may reflect an IP subnet for each network. The candidate should be able to determine available IP addresses from a given subnet.

1.03 - Interpret address and subnet relationships

https://www.cisco.com/c/en/us/support/docs/ip/routing-information-protocol-rip/13788-3.html

IP subnets and addresses

A network mask helps you know which portion of the address identifies the network and which portion of the address identifies the node. Class A, B, and C networks have default masks, also known as natural masks, as shown here:

A network mask helps you know which portion of the address identifies the network and which portion of the address identifies the node. Class A, B, and C networks have default masks, also known as natural masks, as shown here:

| Class A: | 255.0.0.0 |

|---|---|

| Class B: | 255.255.0.0 |

| Class C: | 255.255.255.0 |

An IP address on a Class A network that has not been subnetted would have an address/mask pair similar to: 8.20.15.1 255.0.0.0. To see how the mask helps you identify the network and node parts of the address, convert the address and mask to binary numbers.

8.20.15.1 = 00001000.00010100.00001111.00000001

255.0.0.0 = 11111111.00000000.00000000.00000000

Once you have the address and the mask represented in binary, then identifying the network and host ID is easier. Any address bits that have corresponding mask bits set to 1 represent the network ID. Any address bits that have corresponding mask bits set to 0 represent the node ID.

| 8.20.15.1 = | 00000001 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 255.0.0.0 = | 00000000 | |||

| Net id | Host id |

Understanding Subnetting

Subnetting allows you to create multiple logical networks that exist within a single Class A, B, or C network. If you do not subnet, you are only able to use one network from your Class A, B, or C network, which is unrealistic.

Each data link on a network must have a unique network ID, with every node on that link being a member of the same network. If you break a major network (Class A, B, or C) into smaller subnets, it allows you to create a network of interconnecting subnets. Each data link on this network would then have a unique network/sub-network ID. Any device, or gateway, connecting n networks/subnets has n distinct IP addresses, one for each network / sub-network that it interconnects. In order to subnet a network, extend the natural mask using some of the bits from the host ID portion of the address to create a sub-network ID. For example, given a Class C network of 204.17.5.0, which has a natural mask of 255.255.255.0, you can create subnets in this manner:

| 204.17.5.0 | 00000000 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 255.255.255.224 | 11100000 | |||

| subnet |

By extending the mask to be 255.255.255.224, you have taken three bits (indicated by “sub”) from the original host portion of the address and used them to make subnets. With these three bits, it is possible to create eight subnets. With the remaining five host ID bits, each subnet can have up to 32 host addresses, 30 of which can actually be assigned to a device since host ids of all zeros or all ones are not allowed (it is very important to remember this). So, with this in mind, these subnets have been created.

| 204.17.5.0 | 255.255.255.224 | host address range 1 to 30 |

|---|---|---|

| 204.17.5.32 | 255.255.255.224 | host address range 33 to 62 |

| 204.17.5.64 | 255.255.255.224 | host address range 65 to 94 |

| 204.17.5.96 | 255.255.255.224 | host address range 97 to 126 |

| 204.17.5.128 | 255.255.255.224 | host address range 129 to 158 |

| 204.17.5.160 | 255.255.255.224 | host address range 161 to 190 |

| 204.17.5.192 | 255.255.255.224 | host address range 193 to 222 |

| 204.17.5.224 | 255.255.255.224 | host address range 225 to 254 |

1.03 - Understand public/private, multicast addressing, and broadcast

https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc1918

Public and Private IP addresses

This link to RFC1918 describes address allocation for private internets. In summary, IPv4 has a relatively small number of available IP addresses, when you think about every IP addressable node in the world. To initially try to relieve the pressure on the available IP address space the RFC1918 set the standard for Private IP addresses. This basically provided the ability for a few ranges of IP addresses to be reserved for private networks. Which meant that since they were not routed publicly on the Internet, the reserved private IP address ranges could be used within each private internet or what is referred to as an intranet without affecting the rest of the Internet. The IP address subnets that are routed on the Internet are considered public IP space and these reserved IP ranges are considered private.

RFC1918 - Private Address Space

The Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA) has reserved the following three blocks of the IP address space for private internets:

10.0.0.0 - 10.255.255.255 (10/8 prefix)

172.16.0.0 - 172.31.255.255 (172.16/12 prefix)

192.168.0.0 - 192.168.255.255 (192.168/16 prefix)

We will refer to the first block as “24-bit block”, the second as “20-bit block”, and to the third as “16-bit” block. Note that (in pre-CIDR notation) the first block is nothing but a single class A network number, while the second block is a set of 16 contiguous class B network numbers, and third block is a set of 256 contiguous class C network numbers.

An enterprise that decides to use IP addresses out of the address space defined in this document can do so without any coordination with IANA or an Internet registry. The address space can thus be used by many enterprises. Addresses within this private address space will only be unique within the enterprise, or the set of enterprises which choose to cooperate over this space so they may communicate with each other in their own private internet.

As before, any enterprise that needs globally unique address space is required to obtain such addresses from an Internet registry. An enterprise that requests IP addresses for its external connectivity will never be assigned addresses from the blocks defined above.

In order to use private address space, an enterprise needs to determine which hosts do not need to have network layer connectivity outside the enterprise in the foreseeable future and thus could be classified as private. Such hosts will use the private address space defined above. Private hosts can communicate with all other hosts inside the enterprise, both public and private. However, they cannot have IP connectivity to any host outside of the enterprise. While not having external (outside of the enterprise) IP connectivity private hosts can still have access to external services via mediating gateways (e.g., application layer gateways).

All other hosts will be public and will use globally unique address space assigned by an Internet Registry. Public hosts can communicate with other hosts inside the enterprise both public and private and can have IP connectivity to public hosts outside the enterprise. Public hosts do not have connectivity to private hosts of other enterprises.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Multicast_address

Multicast Addressing

A multicast address is a logical identifier for a group of hosts in a computer network that are available to process datagrams or frames intended to be multicast for a designated network service. The CIDR notation for this group is 224.0.0.0/4. The group includes the addresses from 224.0.0.0 to 239.255.255.255. Address assignments from within this range are specified in RFC 5771.

https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc5771

The address range is divided into blocks each assigned a specific purpose or behavior.

| IP multicast address range | Description | Routable |

| 224.0.0.0 to 224.0.0.255 | Local subnetwork[1] | No |

| 224.0.1.0 to 224.0.1.255 | Internetwork control | Yes |

| 224.0.2.0 to 224.0.255.255 | AD-HOC block 1[2] | Yes |

| 224.3.0.0 to 224.4.255.255 | AD-HOC block 2[3] | Yes |

| 232.0.0.0 to 232.255.255.255 | Source-specific multicast[1] | Yes |

| 233.0.0.0 to 233.251.255.255 | GLOP addressing[4] | Yes |

| 233.252.0.0 to 233.255.255.255 | AD-HOC block 3[5] | Yes |

| 234.0.0.0 to 234.255.255.255 | Unicast-prefix-based | Yes |

| 239.0.0.0 to 239.255.255.255 | Administratively scoped[1] | Yes |

https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc3306

Multicast addresses in IPv6 use the prefix ff00::/8. IPv6 multicast addresses can be structured the new format RFC 3306, updated by RFC 7371..

General multicast address format (new)

| Bits | 8 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 64 | 32 |

| Field | prefix | ff1 | scope | ff2 | reserved | plen | network prefix | group ID |

https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc919

Broadcast IP

RFC 919 defines the need for a broadcast IP address on each LAN. This is essentially a reserved IP address in every subnet that when used as a destination IP address would allow the sending system to speak to everyone in the subnet at the same time. Much like an all f’s MAC address at layer 2. The IP reserved and is always the highest IP of the subnet (example 192.168.1.255/24).

1.03 - Explain the function and purpose of NAT and of DHCP

https://support.f5.com/csp/article/K41572395

Purpose of NAT

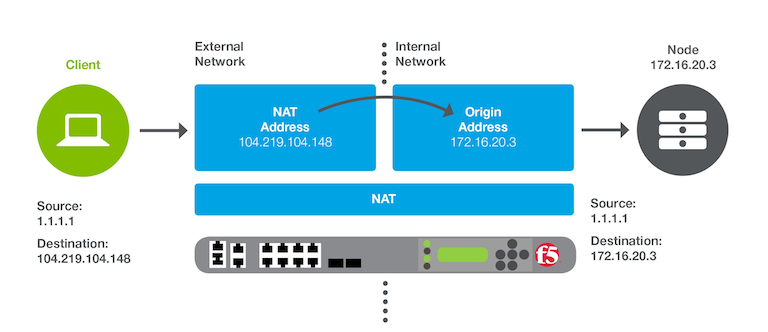

A Network Address Translation (NAT) is a mapping of one IP address to another IP address. This mapping can be a translation of source, destination, or both. A NAT can be outbound or inbound.

Outbound NAT

Outbound NAT translates an internal source address to a public address. A NAT can also be used to translate an internal node’s IP address to an Internet routable IP address.

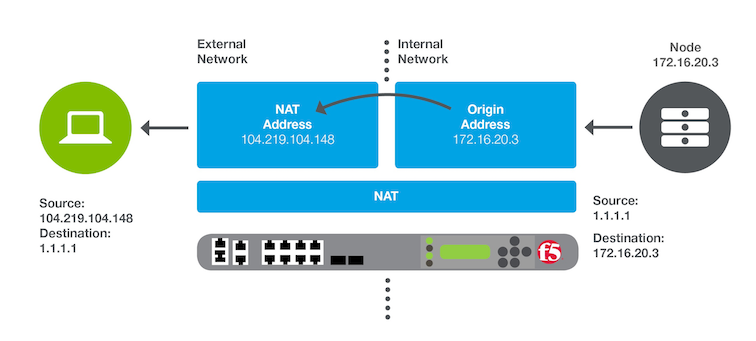

Inbound NAT

Inbound NAT translates a public destination address to an internal address. When an external client sends traffic to the public IP address defined in a NAT, BIG-IP translates that destination address to the internal node IP address.

https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc2131

Purpose of DHCP

The Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol (DHCP) provides configuration parameters to Internet hosts. DHCP consists of two components: a protocol for delivering host-specific configuration parameters from a DHCP server to a host and a mechanism for allocation of network addresses to hosts.

DHCP is built on a client-server model, where designated DHCP server hosts allocate network addresses and deliver configuration parameters to dynamically configured hosts. Throughout the remainder of this document, the term “server” refers to a host providing initialization parameters through DHCP, and the term “client” refers to a host requesting initialization parameters from a DHCP server.

A host should not act as a DHCP server unless explicitly configured to do so by a system administrator. The diversity of hardware and protocol implementations in the Internet would preclude reliable operation if random hosts were allowed to respond to DHCP requests. For example, IP requires the setting of many parameters within the protocol implementation software. Because IP can be used on many dissimilar kinds of network hardware, values for those parameters cannot be guessed or assumed to have correct defaults. Also, distributed address allocation schemes depend on a polling/defense mechanism for discovery of addresses that are already in use. IP hosts may not always be able to defend their network addresses, so that such a distributed address allocation scheme cannot be guaranteed to avoid allocation of duplicate network addresses.

DHCP supports three mechanisms for IP address allocation. In “automatic allocation”, DHCP assigns a permanent IP address to a client. In “dynamic allocation”, DHCP assigns an IP address to a client for a limited period of time (or until the client explicitly relinquishes the address). In “manual allocation”, a client’s IP address is assigned by the network administrator, and DHCP is used simply to convey the assigned address to the client. A particular network will use one or more of these mechanisms, depending on the policies of the network administrator.

Dynamic allocation is the only one of the three mechanisms that allows automatic reuse of an address that is no longer needed by the client to which it was assigned. Thus, dynamic allocation is particularly useful for assigning an address to a client that will be connected to the network only temporarily or for sharing a limited pool of IP addresses among a group of clients that do not need permanent IP addresses. Dynamic allocation may also be a good choice for assigning an IP address to a new client being permanently connected to a network where IP addresses are sufficiently scarce that it is important to reclaim them when old clients are retired. Manual allocation allows DHCP to be used to eliminate the error-prone process of manually configuring hosts with IP addresses in environments where (for whatever reasons) it is desirable to manage IP address assignment outside of the DHCP mechanisms.

The format of DHCP messages is based on the format of BOOTP messages, to capture the BOOTP relay agent behavior described as part of the BOOTP specification [7, 21] and to allow interoperability of existing BOOTP clients with DHCP servers. Using BOOTP relay agents eliminates the necessity of having a DHCP server on each physical network segment.

Managing IP addresses for DHCP clients

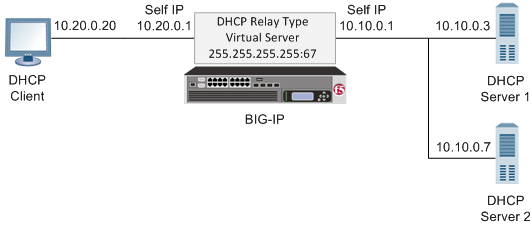

When you want to manage Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol (DHCP) client IP addresses, you can configure the BIG-IP system to act as a DHCP relay agent. A common reason to configure the BIG-IP system as a DHCP relay agent is when the DHCP clients reside on a different subnet than the subnet of the DHCP servers.

About the BIG-IP system as a DHCP relay agent

A BIG-IP virtual server, configured as a Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol (DHCP) type, provides you with the ability to relay DHCP client requests for an IP address to one or more DHCP servers, available as pool members in a DHCP pool, on different +virtual local area networks (VLANs). The DHCP client request is relayed to all pool members, and the replies from all pool members are relayed back to the client.

A sample DHCP relay agent configuration

For example, a DHCP client sends a broadcast message to the destination IP address 255.255.255.255, which is the destination address configured on the virtual server. A DHCP type virtual server automatically uses port 67 for an IPv4 broadcast message or port 547 for an IPv6 broadcast message. The BIG-IP virtual server receives this message on the VLAN with self IP address 10.20.0.1 and relays the DHCP request to all DHCP servers: 10.10.0.3 and 10.10.0.7.

All DHCP servers provide a DHCP response with available IP addresses to the BIG-IP virtual server, which then relays all responses to the client. The client accepts and uses only one of the IP addresses received.

Note: In this example, there is no hop between the DHCP client and the BIG-IP relay agent. However, a common topology is one that includes this hop, which is often another BIG-IP system.

1.03 - Determine valid address IPv6

https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc2373

http://www.ciscopress.com/articles/article.asp?p=2803866

IPv6

This Cisco Press link is better reading than the RFC2373 for a clear understanding of IPv6 address representation. I doubt that you will be required to know how to do IPv6 subnetting or any in depth IP calculations during this exam but being able to recognize valid representations of IPv6 addresses will be essential. You should familiarize yourself with IPv6. Remember that the BIG-IP operating system is native IPv6.

IPv6 addresses are 128 bits in length and written as a string of hexadecimal digits. Every 4 bits can be represented by a single hexadecimal digit, for a total of 32 hexadecimal values. The alphanumeric characters used in hexadecimal are not case sensitive; therefore, uppercase and lowercase characters are equivalent. Although IPv6 address can be written in lowercase or uppercase, RFC 5952, A Recommendation for IPv6 Address Text Representation, recommends that IPv6 addresses be represented in lowercase. As described in RFC 4291, the preferred form is x:x:x:x:x:x:x:x. Each x is a 16-bit section that can be represented using up to four hexadecimal digits, with the sections separated by colons.

Objective - 1.04 State the service that ARP provides¶

1.04 - Identify a valid MAC address

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MAC_address

MAC Address

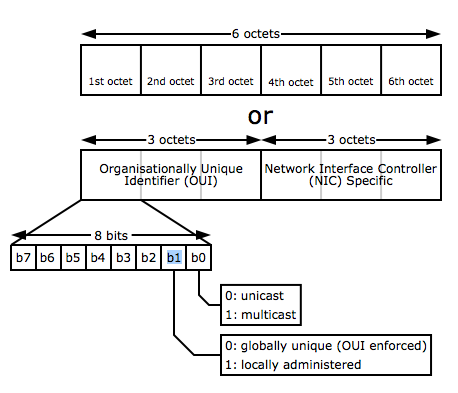

A media access control address (MAC address) is a unique identifier assigned to a network interface controller (NIC) for use as a network address in communications within a network segment. This use is common in most IEEE 802 networking technologies, including Ethernet, Wi-Fi, and Bluetooth. Within the Open Systems Interconnection (OSI) network model, MAC addresses are used in the medium access control protocol sublayer of the data link layer. As typically represented, MAC addresses are recognizable as six groups of two hexadecimal digits, separated by hyphens, colons, or without a separator. In hexadecimal the broadcast address would be FF:FF:FF:FF:FF:FF.

MAC addresses are primarily assigned by device manufacturers and are therefore often referred to as the burned-in address, or as an Ethernet hardware address, hardware address, and physical address. Each address can be stored in hardware, such as the card’s read-only memory, or by a firmware mechanism. Many network interfaces however support changing their MAC address. The address typically includes a manufacturer’s organizationally unique identifier (OUI). MAC addresses are formed according to the principles of two numbering spaces based on Extended Unique Identifiers (EUI) managed by the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE)

1.04 - Define ARP and explain what it does

https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc826

http://linux-ip.net/html/ether-arp.html

ARP

ARP defines the exchanges between network interfaces connected to an Ethernet media segment in order to map an IP address to a link layer address on demand. Link layer addresses are hardware addresses (although they are not immutable) on Ethernet cards and IP addresses are logical addresses assigned to machines attached to the Ethernet. Link layer addresses may be known by many different names: Ethernet addresses, Media Access Control (MAC) addresses, and even hardware addresses.

Address Resolution Protocol (ARP) exists solely to glue together the IP and Ethernet networking layers. Since networking hardware such as switches, hubs, and bridges operate on Ethernet frames, they are unaware of the higher layer data carried by these frames. Similarly, IP layer devices, operating on IP packets need to be able to transmit their IP data on Ethernets. ARP defines the conversation by which IP capable hosts can exchange mappings of their Ethernet and IP addressing.

ARP is used to locate the Ethernet address associated with a desired IP address. When a machine has a packet bound for another IP on a locally connected Ethernet network, it will send a broadcast Ethernet frame containing an ARP request onto the Ethernet. All machines with the same Ethernet broadcast address will receive this packet. If a machine receives the ARP request and it hosts the IP requested, it will respond with the link layer address on which it will receive packets for that IP address.

Once the requestor receives the response packet, it associates the MAC address and the IP address. This information is stored in the ARP cache.

1.04 - State the purpose of a default gateway

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Default_gateway

Default Gateway

A default gateway is the node in a computer network using the internet protocol suite that serves as the forwarding host (router) to other networks, when no other route specification matches the destination IP address of a packet.

Objective - 1.05 Given a scenario, establish required routing¶

1.05 - Given a scenario, establish required routing

Possible Required Routing

There are many different deployment scenarios that will each demand their own unique configuration and when deploying the BIG-IP system or adding to the network configuration of the system additional routes may be needed for proper communications. This exam will possibly provide a deployment scenario and ask what additional routes need to be added to the BIG-IP’s configuration for the deployment to work correctly.

1.05 - Explain why a route is needed

Routing and Why Routes Are Needed

Routing is the process of selecting a path for traffic between networks or across multiple networks. If a network device needs to communicate with another device off of its local area network (LAN), it must know a way to get there. For a node with a single network interface on a LAN, it will normally just be to the router acting as a default gateway for the IP subnet. But some network devices have multiple network interfaces on different networks to use or have the responsibility of routing traffic in the network and the next hop to get to a particular destination may be out a particular interface. The list of which way to go to get to the different destination IP addresses is known as a route table. Static routes can be added to a systems route table which will allow it to know which way to go to get to all of the IP subnets in a network, but the management of such a large table would be daunting and very inefficient. And if a device failed in the path to a destination, the system would lose communications with the destination until the path recovered or was manually edited by an administrator to use a different path that may be available. This is where dynamic routing attempts to solve the administrative inefficiency problem by constructing routing tables automatically, based on information learned by routing protocols. This allows devices on the network to act nearly autonomously in avoiding network failures and blockages.

The BIG-IP system may need to have static routes defined to make traffic flow out a particular network interface rather than to the default gateway to reach the intended destination. An example would be needing to monitor an application or node that is not on the locally attached subnets of the system and the default gateway has no path to the destination but a separate router on another local subnet can reach the destination.

By enabling and configuring any of the BIG-IP advanced routing modules, you can configure dynamic routing on the BIG-IP system. You enable one or more advanced routing modules, as well as the Bidirectional Forwarding Detection (BFD) protocol, on a per-route-domain basis. Advanced routing module configuration on the BIG-IP system provides these functions:

- Dynamically adds routes to the Traffic Management Microkernel (TMM) and host route tables.

- Advertises and redistributes routes for BIG-IP virtual addresses to other routers.

- When BFD is enabled, detects failing links more quickly than would normally be possible using the dynamic routing protocols’ own detection mechanisms.

The BIG-IP advanced routing modules support these protocols.

Dynamic routing protocols

| Protocol Name | Description | Daemon | IP version supported |

| BFD | Bidirectional Forwarding Detection is a protocol that detects faults between two forwarding engines connected by a link. On the BIG-IP system, you can enable the BFD protocol for the OSPFv2, BGP4, and IS-IS dynamic routing protocols specifically. | oamd | IPv4 and IPv6 |

| BGP4 | Border Gateway Protocol (BGP) with multi-protocol extension is a dynamic routing protocol for external networks that supports the IPv4 and IPv6 addressing formats. | bgpd | IPv4 and IPv6 |

| IS-IS | Intermediate System-to-Intermediate System (IS-IS) is a dynamic routing protocol for internal networks, based on a link-state algorithm. | isisd | IPv4 and IPv6 |

| OSPFv2 | The Open Shortest Path First (OSPF) protocol is a dynamic routing protocol for internal networks, based on a link-state algorithm. | ospfd | IPv4 |

| OSPFv3 | The OSPFv3 protocol is an enhanced version of OSPFv2. | ospf6d | IPv6 |

| PIM | The Protocol Independent Multicast (PIM) protocol is a dynamic routing protocol for multicast packets from a server to all interested clients. | pimd | IPv4 and IPv6 |

| RIPv1/RIPv2 | Routing Information Protocol (RIP) is a dynamic routing protocol for internal networks, based on a distance-vector algorithm (number of hops). | ripd | IPv4 |

| RIPng | The RIPng protocol is an enhanced version of RIPv2. | ripngd | IPv6 |

1.05 - Explain network hops

Network Hops

Network hops refers to the number of networking devices between the sending unit and the final destination of the communication. Some or all of these devices can make changes to the datagram in the flow and some dynamic routing protocols use hop count as a metric in determining the best path.

1.05 - Given a destination IP address and current routing table, identify a route to be used

https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/previous-versions/windows/it-pro/windows-server-2003/cc779122(v=ws.10)?redirectedfrom=MSDN

Route Tables

Every computer that runs TCP/IP makes routing decisions. The IP routing table controls these decisions. To display the IP routing table on computers running Windows Server 2003 operating systems, you can type “route print” at a command prompt.

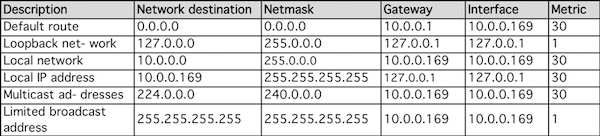

The following table shows an example of an IP routing table. This example is for a computer running Windows Server 2003, Standard Edition with one 100 megabit per second (Mb/s) network adapter and the following configuration:

- IP address: 10.0.0.169

- Subnet mask: 255.0.0.0

- Default gateway: 10.0.0.1

The routing table is built automatically, based on the current TCP/IP configuration of your computer. Each route occupies a single line in the displayed table. Your computer searches the routing table for an entry that most closely matches the destination IP address.

Your computer uses the default route if no other host or network route matches the destination address included in an IP datagram. The default route typically forwards an IP datagram (for which there is no matching or explicit local route) to a default gateway address for a router on the local subnet. In the previous example, the default route forwards the datagram to a router with a gateway address of 10.0.0.1.

Because the router that corresponds to the default gateway contains information about the network IDs of the other IP subnets within the larger TCP/IP Internet, it forwards the datagram to other routers until the datagram is eventually delivered to an IP router that is connected to the specified destination host or subnet within the larger network.

The following sections describe each of the columns displayed in the IP routing table: network destination, netmask, gateway, interface, and metric.

Network destination

The network destination is used with the netmask to match the destination IP address. The network destination can range from 0.0.0.0 for the default route through 255.255.255.255 for the limited broadcast, which is a special broadcast address to all hosts on the same network segment.

Gateway

The gateway address is the IP address that the local host uses to forward IP datagrams to other IP networks. This is either the IP address of a local network adapter or the IP address of an IP router (such as a default gateway router) on the local network segment.

Interface

The interface is the IP address that is configured on the local computer for the local network adapter that is used when an IP datagram is forwarded on the network.

Metric

A metric indicates the cost of using a route, which is typically the number of hops to the IP destination. Anything on the local subnet is one hop, and each router crossed after that is an additional hop. If there are multiple routes to the same destination with different metrics, the route with the lowest metric is selected.

Objective - 1.06 Define ADC application objects¶

1.06 - Define ADC application objects

https://techdocs.f5.com/kb/en-us/products/big-ip_ltm/manuals/product/ltm-basics-13-0-0.html

Application Delivery Controller Objects

The BIG-IP system uses configuration-based objects within the system configuration to represent the different functional parts that control the flow and process of the application as it passes through the BIG-IP. From Virtual Servers that act as the listener which takes in the inbound connection and depicts how the traffic will be processed through the use of Profiles and then passed to the Pool which handles the load distribution across the Pool Members made up of Nodes that represent the application servers themselves, every object has a purpose. Understanding all of the different types of objects, how they are used, and their functional purpose will be necessary knowledge for this exam.

1.06 - Define load balancing including intelligent load balancing and server selection

Distribution of Load

The amount of connections and utilization that an application may have coming in from its core base of users can often far exceed the throughput capacity of a single server hosting the application. The need for distributing the inbound requests and processing load of responses across a group of servers running the same application or service is self-evident. The trick to distributing the load is finding the right load balancing solution and then implementing it in the most effective manner. While making sure the functions of the applications are not being broken as users are sent all across the servers in the group.

Load balancing is an integral part of the BIG-IP system. Configuring load balancing on a BIG-IP system means determining your load balancing scenario, that is, which pool member should receive a connection hosted by a particular virtual server. Once you have decided on a load balancing scenario, you can specify the appropriate load balancing method for that scenario.

A load balancing method is an algorithm or formula that the BIG-IP system uses to determine the server to which traffic will be sent. Individual load balancing methods take into account one or more dynamic factors, such as current connection count. Because each application of the BIG-IP system is unique, and server performance depends on a number of different factors, we recommend that you experiment with different load balancing methods, and select the one that offers the best performance in your particular environment.

Default load balancing method

The default load balancing method for the BIG-IP system is Round Robin, which simply passes each new connection request to the next server in line. All other load balancing methods take server capacity and or status into consideration.

If the equipment that you are load balancing is roughly equal in processing speed and memory, Round Robin method works well in most configurations. If you want to use the Round Robin method, you can skip the remainder of this section, and begin configuring other pool settings that you want to add to the basic pool configuration.

BIG-IP system load balancing methods

The BIG-IP system provides several load balancing methods for load balancing traffic to pool members.

| Method | Description | When to use |

| Round Robin | This is the default load balancing method. Round Robin method passes each new connection request to the next server in line, eventually distributing connections evenly across the array of machines being load balanced. | Round Robin method works well in most configurations, especially if the equipment that you are load balancing is roughly equal in processing speed and memory. |

| Ratio (member) Ratio (node) | The BIG-IP system distributes connections among pool members or nodes in a static rotation according to ratio weights that you define. In this case, the number of connections that each system receives over time is proportionate to the ratio weight you defined for each pool member or node. You set a ratio weight when you create each pool member or node. | These are static load balancing methods, basing distribution on user-specified ratio weights that are proportional to the capacity of the servers. |

| Dynamic Ratio (member) Dynamic Ratio (node) | The Dynamic Ratio methods select a server based on various aspects of real-time server performance analysis. These methods are similar to the Ratio methods, except that with Dynamic Ratio methods, the ratio weights are system-generated, and the values of the ratio weights are not static. These methods are based on continuous monitoring of the servers, and the ratio weights are therefore continually changing.

|

The Dynamic Ratio methods are used specifically for load balancing traffic to RealNetworks RealSystem Server platforms, Windows platforms equipped with Windows Management Instrumentation (WMI), or any server equipped with an SNMP agent such as the UC Davis SNMP agent or Windows 2000 Server SNMP agent. |

| Fastest (node) Fastest (application) | The Fastest methods select a server based on the least number of current sessions. These methods require that you assign both a Layer 7 and a TCP type of profile to the virtual server.

|

The Fastest methods are useful in environments where nodes are distributed across separate logical networks. |

| Least Connections (member) Least Connections (node) | The Least Connections methods are relatively simple in that the BIG-IP system passes a new connection to the pool member or node that has the least number of active connections.

|

The Least Connections methods function best in environments where the servers have similar capabilities. Otherwise, some amount of latency can occur. For example, consider the case where a pool has two servers of differing capacities, A and B. Server A has 95 active connections with a connection limit of 100, while server B has 96 active connections with a much larger connection limit of 500. In this case, the Least Connections method selects server A, the server with the lowest number of active connections, even though the server is close to reaching capacity. If you have servers with varying capacities, consider using the Weighted Least Connections methods instead. |

| Weighted Least Connections (member) Weighted Least Connections (node) | Similar to the Least Connections methods, these load balancing methods select pool members or nodes based on the number of active connections. However, the Weighted Least Connections methods also base their selections on server capacity. The Weighted Least Connections (member) method specifies that the system uses the value you specify in Connection Limit to establish a proportional algorithm for each pool member. The system bases the load balancing decision on that proportion and the number of current connections to that poolmember. For example, member_a has 20 connections and its connection limit is 100, so it is at 20% of capacity. Similarly, member_b has 20 connections and its connection limit is 200, so it is at 10% of capacity. In this case,the system select selects member_b. This algorithm requires all pool members to have a non-zero connection limit specified. The Weighted Least Connections (node) method specifies that the system uses the value you specify in the node’s Connection Limit setting and the number of current connections to a node to establish a proportional algorithm. This algorithm requires all nodes used by pool members to have a non-zero connection limit specified. If all servers have equal capacity, these load balancing methods behave in the same way as the Least Connections methods.

|

Weighted Least Connections methods work best in environments where the servers have differing capacities. For example, if two servers have the same number of active connections but one server has more capacity than the other, the BIG-IP system calculates the percentage of capacity being used on each server and uses that percentage in its calculations. |

| Observed (member) Observed (node) |

|

The need for the Observed methods is rare, and they are not recommended for large pools. |

| Predictive (member) Predictive (node) | The Predictive methods use the ranking methods used by the Observed methods, where servers are rated according to the number of current connections. However, with the Predictive methods, the BIG-IP system analyzes the trend of the ranking over time, determining whether a node’s performance is currently improving or declining. The servers with performance rankings that are currently improving, rather than declining, receive a higher proportion of the connections. | The need for the Predictive methods is rare, and they are not recommend for large pools. |

| Least Sessions | The Least Sessions method selects the server that currently has the least number of entries in the persistence table. Use of this load balancing method requires that the virtual server reference a type of profile that tracks persistence connections, such as the Source Address Affinity or Universal profile type. Note: The Least Sessions methods are incompatible with cookie persistence. |

The Least Sessions method works best in environments where the servers or other equipment that you are load balancing have similar capabilities. |

| Ratio Least Connections | The Ratio Least Connections methods cause the system to select the pool member according to the ratio of the number of connections that each pool member has active. |

1.06 - Explain features of an application delivery controller

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Application_delivery_controller#ADC_Vendors

Application Delivery Controllers

A common misconception is that an Application Delivery Controller (ADC) is an advanced load-balancer. This is not an adequate description. An ADC is a network device that helps applications to direct user traffic in order to remove the excess load from two or more servers. In fact, an ADC includes many OSI layer 3-7 services which happen to include load-balancing. Other features commonly found in most ADCs include SSL offload, Web Application Firewall, NAT64, DNS64, and proxy/reverse proxy to name a few. They also tend to offer more advanced features such as content redirection as well as server health monitoring.

1.06 - Explain benefits of an application delivery controller

https://devcentral.f5.com/s/articles/6-reasons-you-need-an-application-delivery-controller-now

Some of the Benefits of an ADC

An application delivery controller can solve many problems that arise in your application environment

Efficiency

An application delivery controller (ADC) can improve the efficiency of the servers for which it manages application requests. By offloading compute intensive processing like SSL or TCP/IP connection management an ADC reduces the overhead associated with assembling and serving responses to application requests and makes better use of the resources (RAM, CPU, I/O) on each server. Making your infrastructure more efficient is also a great way to “go green”.

Performance

The performance of your applications can be improved dramatically through the deployment of an ADC. Whether it’s because of compression, caching, protocol optimizations, connection management or intelligent load balancing algorithms, an ADC improves the overall performance of your applications.

Reliability

If you rely on applications for business processes or as a revenue stream, the last thing you want is for those application to be unavailable. An ADC provides reliability by ensuring that requests are sent only to available servers, redirecting requests when a server is down for maintenance or finally hit the wall and died.

If you’re large enough to have two data centers, an ADC with global load balancing capabilities furthers assurance of reliability by redirecting requests from the primary data center to a secondary in the event of a disaster - whether that’s a natural disaster (earthquake, fire, flood) or man-made (oops - was that our DS3 I just ripped out?).

Security

We’re not talking about advanced security options like web application firewalls or secure remote access products such as an SSL VPN, we’re just talking basic security here. DDoS protection, rate limiting, blacklisting, whitelisting, authentication, resource obfuscation, SSL, content encryption - the bare minimum security you need to protect your applications and the servers on which they’re deployed. An ADC provides the core security functions you need to ensure your site is safe.

Capacity

Capacity is about how much throughput, how many requests, how many users you can support. It’s nearly impossible to support thousands of concurrent users with a single server, unless it’s one really really really big server. You need more than one server, and in order to architect a solution that uses a pool of servers you need something to mediate and direct those requests - to balance the load across those servers. That means you need an ADC, because the core purpose of an ADC is to perform load balancing and ensure that you can serve everyone who wants to be served.

Scalability

Scaling up to meet demand is difficult, doing so without re-architecting your infrastructure or scheduling down-time is even more difficult. By including an ADC in your architecture from the very beginning, the process becomes a simple one. Add a new server, add it to the ADC and voila! You’ve just scaled up and can instantly support more users and more requests without requiring downtime or moving around network cables.